In the beginning was the bird

A Biographical and Territorial Perch

Artist and musician, Michael Pestel, was born in Hildesheim, Germany in 1950. During his early years, he translated diverse avian languages for anyone who would listen. Indeed, Birdspeak was his first language, German his second, English his third, and Japanese his fourth. However, by the time he arrived in the States at age six, avian linguistics had nearly vanished into thin air, subsumed as they were by the human-centered grammars of growing up. It would be thirty-five years before Pestel accidentally rediscovered his love for birds, and the ability to whistle and whisper in their direction.

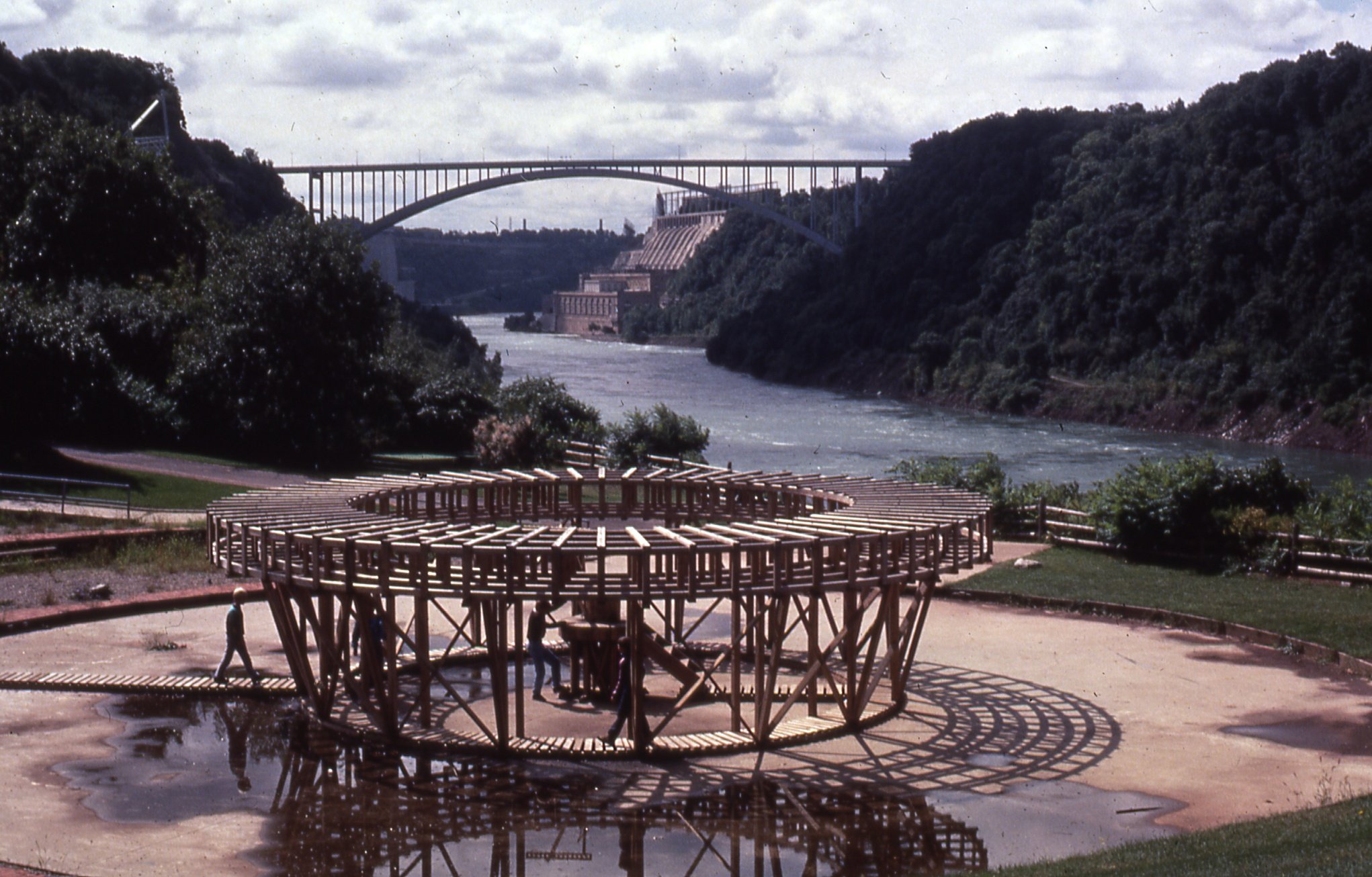

Sine Wave (Avian Truss), 1986

Sighting Wheel, 1985

Then something happened that changed everything…

In the meantime, Pestel studied a diversity of subjects in his student years. Music, writing, religious studies, English and German literature, Japanese language and culture, architecture, sculpture, art history… everything but birds. He eventually landed on sculpture, first in the vein of Brancusi and then structural, site-specific architectural works made predominantly out of wood. In 1978, he received an MFA from the Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles before going on to teach a wide array of subjects in art departments and art schools here and abroad. Those subjects included art history, sculpture, architectural design, sound and performance art. He also began constructing large-scale works of outdoor sculpture – Sightingwheel 1 and 2, Sine Wave, Ohio Gauntlet, Widow’s Walk, Up In Smoke, as well as large indoor projects such as Agronome, Piers Project, Hadrian Spin-Out, and Fountainhead. All of these works, aside from their environmental and historical references, had nothing directly to do with birds. Birds were not on his radar.

On Sunday, April 26, 1992, Pestel rediscovered the language of birds during a performance – a musical conundrum – in the tropical rainforest at the Pittsburgh Aviary. The performance consisted of a cadenced and continuous recitation of the Red List of extinct birds, i.e., the names and dates of 160+ birds we humans have eradicated since the 16th century. For each name, Pestel played a short, un-mimicked flute riff as a stand-in for sounds we can no longer hear. Thus, absence became an entry point into the presence of living birds. Such an experience was tantamount to again falling under the spell of avian wonder some four decades later:

“At #14 Lord Howe Island White-eyes / 1921, a bird high up in the indoor canopy repeats my riff almost verbatim. Such astonishing mimicry comes from more than one bird over the course of a fifty minute performance, and every time it does, my long ago avian memory comes to life. In the decade that follows, I perform with these birds at least once a week. I introduce musicians and dancers to the aviary’s eloquent – and often rambunctious – prisoners. The keepers insist that I am the birds’ Johnny Cash, their wholesome, Folsom savior. But with each musical session, I am also becoming bird… a deeply captivated bird among captured birds. We are both imprisoned in a concert hall of perpetually exotic sounds resonating throughout: an artificial marshland with pond, a steaming rainforest with domed canopy, and smaller-scale caged deserts, mountain-ocean-and grassland scapes, that make up the aviary complex. Here colonialism is at its best with cute, waddling newborn penguins from Patagonia, loquacious White-crested laughing thrushes from Bali, and proud fully-furled peacocks from Sri Lanka. In such a context, my aspirations as a musician can finally take flight and merge seamlessly with those of the visual artist. From this day forward, nearly all of my installations and performances – solo, collaborative, indoors or out – take on an avian raison d’etre.

In jamming live with birds, Pestel extends the compositional spirit of Olivier Messiaen, the greatest composer of bird song in modern history. Where Messiaen brought birds front and center into his compositions for large orchestra and choirs, ensembles, solo piano and organ, Pestel wants to play directly with birds without the separation of either notational interfaces or hermetically sealed concert halls.

An account of Pestel’s years of performing at Pittsburgh’s National Aviary are celebrated in David Rothenberg’s book and his CBC documentary, Why Birds Sing. In addition, bird project collaborations with Dutch eco-artist Jeroen van Westen (Ornithology Series, Birdscape, and Birdscore), as well as with Kudo Taketeru (Stray Birds) , Japan’s leading butoh dancer, have spanned the past thirty years in the USA, Japan, Germany, The Netherlands, Australia, and Colombia. Additional collaborations over the years include those with Moonbob Johnson in Pittsburgh, notably Riverpiano (below), and RiverCube reconnaisance missions on the Allegheny and Connecticut Rivers. In recent years, post-humanist, Cary Wolfe has written a brilliant essay, Requiem: Ectopistes Migratorius (Lafayette College), about Pestel’s installation at Lafayette College. The installation explores the history of the Passenger Pigeon’s demise from five billion in the first quarter of the 19th century, to none by 1914. The essay is one of several in Wolfe’s book, Art and Posthumanism, in a chapter entitled Each Time Unique – The Poetics of Extinction.

Long before birds reappeared in his life, Pestel was already a musician-at-large, performing on the recorder, krummhorn, flute, alto flute, bass flute, soprano sax, piano, and harmonica. But once he began to perform regularly at the aviary, different instrumentation was needed. Hybrid instruments such as the Birdmachine, Birdrawingtable, Pianotable, Violaire, Shengslider, Broominette, Windspinner, Flarinet, and Dopplermarimba were all developed with birdsong, birdsquawk, and birdwings in mind. In addition, an arsenal of bird calls, bird shakers, ocarinas, slide whistles, and world flutes have expanded his repertoire of ornithological sounds. More recently, Pestel has begun playing contr’alto Clarineticut and Aviabraphone (avian-inflected vibraphone).

In July 2023, Pestel, along with ethnomusicologist Alejandra Martinez, visited Colombia’s National Aviary outside of Cartagena. Together they explored avian semiotics of sight and sound, and encountered, in microcosm, the true wealth of an extraordinary country. The aviary is a refuge for rescue birds from throughout Colombia. Many have only one eye or clipped or damaged wings, but their enthusiasm for communicative antics and song is contagious. Watch how Pestel (flute) and Martinez (video) take flight at the Aviario.

Currently, Pestel is working on a permanent outdoor installation and a book, titled AVIARIUM (see video below). The installation part of this project is a performance space dedicated to re-membering and giving voice to the two-hundred or so species we humans have eradicated in the era of global exploration and exploitation. Because the numbers will swell considerably by century’s end, this Aviary will necessarily expand in scope and gravity. In the meantime, AVIARIUM seeks to facilitate interactions between dancers, visual artists, musicians, redwing blackbirds and frogs in and around the pond, and families of wood thrushes who mesmerize the surrounding forest with their crystalline, multiphonic melodies. The written part of the project, The Aviary of Extinct Birds, will be a book of before-and-after birds.

Pestel is the recipient of artist grants and awards from the National Endowment of the Arts, Mondriaan Foundation, German Ministry of Culture, Anser Anser Foundation, Asian Cultural Council, American Institute of Architects, Mellon Foundation, and Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut State Councils on the Arts. Pestel lives on a suburban farm in Middletown, CT with his teenage daughter, two cats, a Labrador retriever, a pond full of frogs, a stream full of prout, a tennis court full of wildflowers, a forest full of mushrooms, and many acres of habitat for birds, foxes, deer, rabbits and other wilden things.